OUR MONASTIC WORK

OUR MONASTIC WORK

Our monastic work and how we help others

The Order of St Benedict, as a monastic sub culture, has three mottoes. The first is Ut in omnibus glorificetur Deus, which is the motivation for the Order’s existence. It means: “So that God may be glorified in all things”. The second is Pax, meaning “peace”, and is the reward hoped for in leading the monastic life. The third is Ora et labora, or “work and pray”, and is what monastics do in order to obtain the first two.

A traditional confusion may arise here. Many people still think that the third motto is Orare est laborare. This means “to work is to pray”, and this is stretching the definition of prayer too far to be safe. Throughout the centuries, monastics have rarely been tempted to neglect work in favour of prayer but neglecting prayer in favour of work has been, and is, a serious danger to them. The origin of this catchphrase lies in the 17th century.

Why do we work?

There are several reasons.

To earn a living

This has been an imperative from the earliest days, in Egypt in the fourth century. Back then, the hermits of the desert made baskets and mats from palm fronds, on the basis that they could exchange them for their necessities.

Later monastics copied books. Being parasitic on secular society was regarded as a disgrace. Monastics have always wished to pay their way, and to find ways to support themselves without compromising their basic way of life. This can be a problem; the parameters of a particular work may change, and threaten the integrity of monastics who have been involved in it. When this happens, the work has to be given up.

To enhance God's Creation

To enhance God’s creation, and secular society’s place in it. This is not just a matter of being part of society’s urge to progress, because not all the values of secular society may help to enhance God’s creation.

In essence, monastics wish to promote what is good and what is beautiful, to the glory of God, again without forgetting their basic call to live a life of prayer in community. Monastics have always been famous for creating truly beautiful landscapes, buildings, works of art and means of worship. But none of these is an end in itself, but a means of enhancing the monastic life of prayer and hence God’s glory.

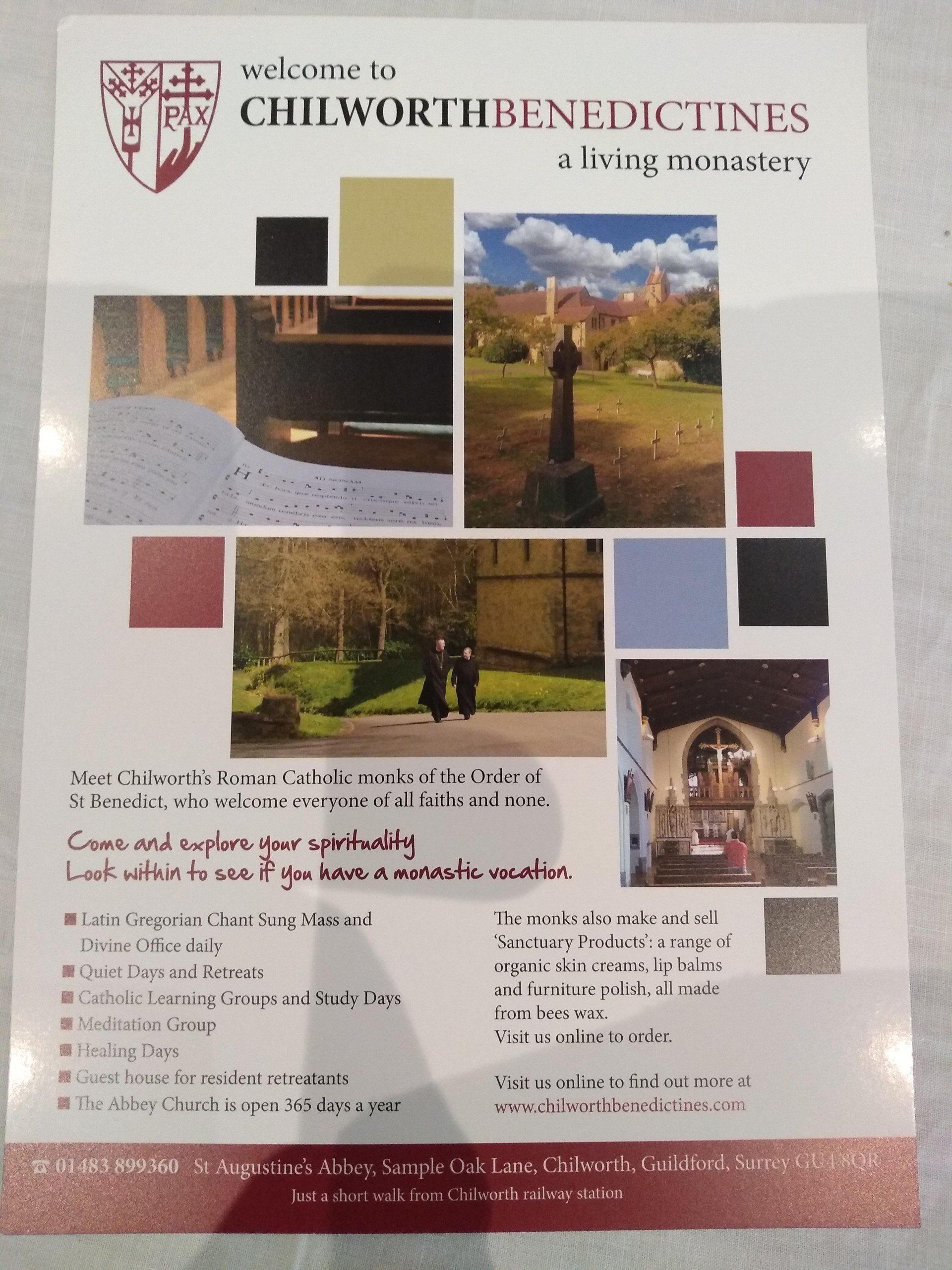

To promote vocations and assist with outreach

To help the individual monastic to persevere in his or her vocation.

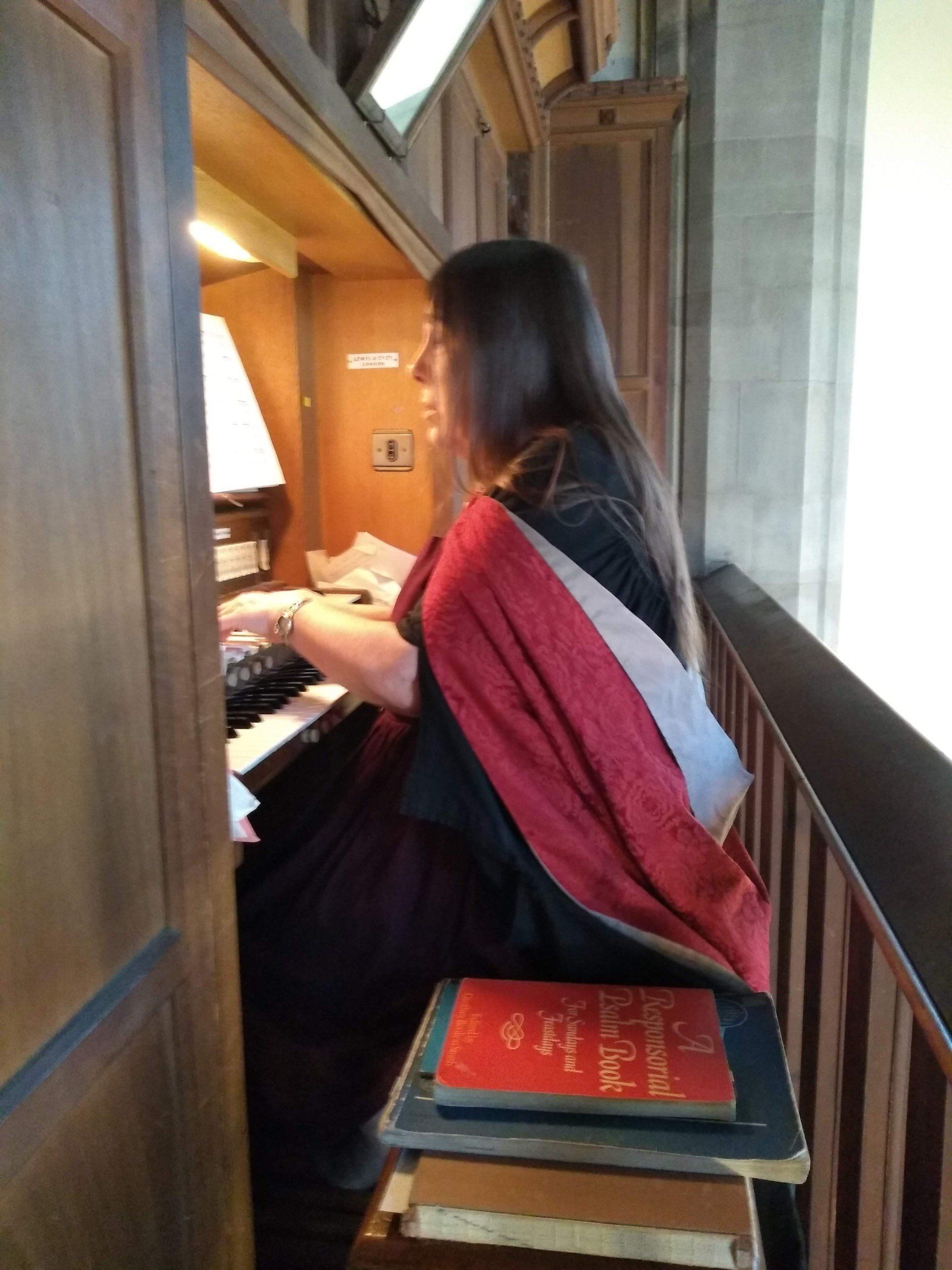

St Antony the Great, one of the first monks in Egypt, had a vision in which an angel instructed him not to try and pray all the time, but to alternate prayer with a routine work which would let the mind rest. This is very good psychology. Monastics do manual work, as distinct from intellectual work, in order to balance mind and body and to keep both healthy. Also, doing work which requires physical effort yet little thought can reveal to the monastic what is lurking in his or her psyche, because in the process many things can arise from the subconscious which need to be prayed about.

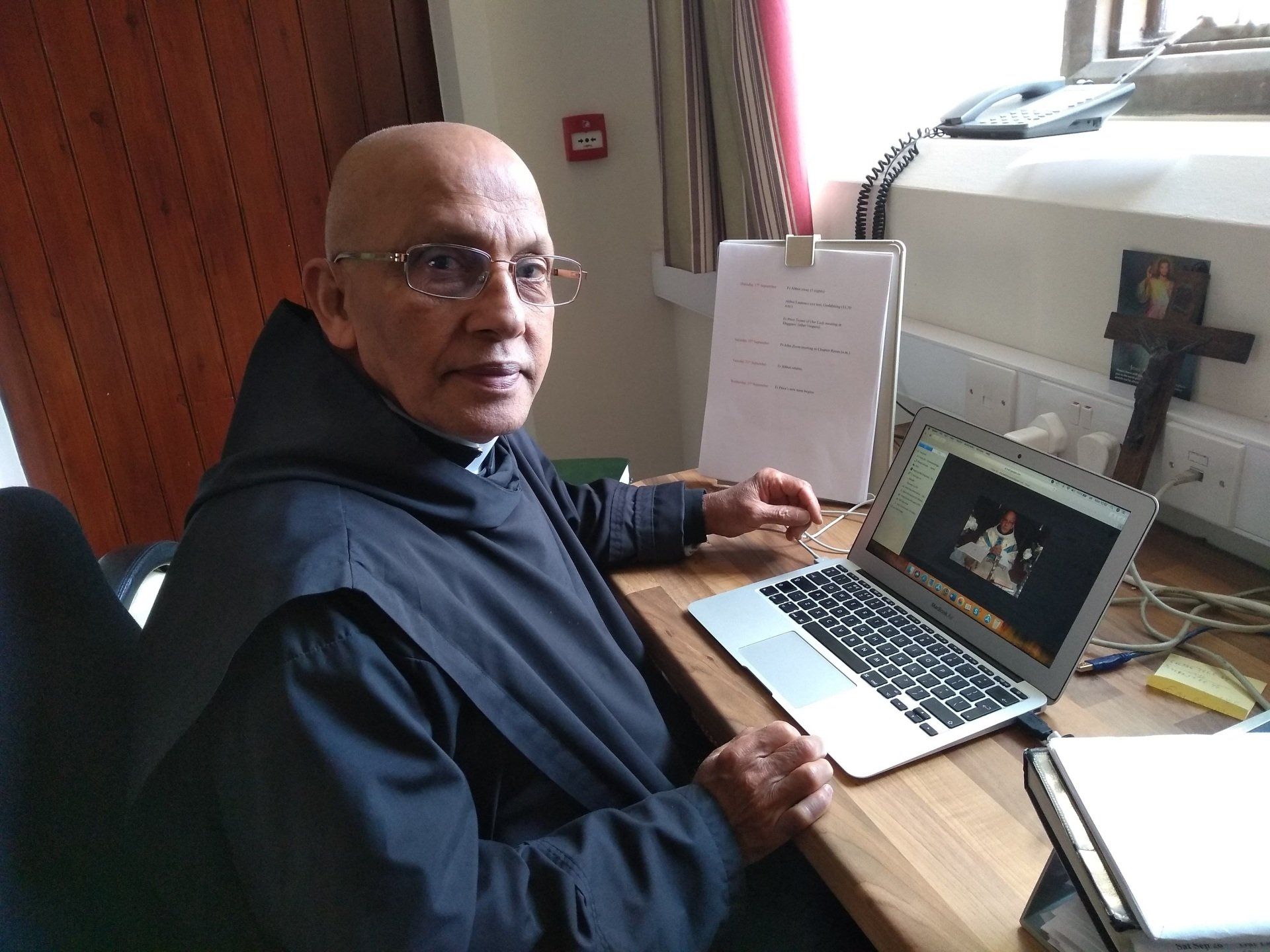

To help the Church in her pastoral outreach.

In missionary lands where there is little or no pastoral structure, monasteries have been extremely effective centres of evangelisation because of their communal witness to higher realities, which can be more important than the preaching of individuals. Throughout history the Church has made use of monastics in building up her pastoral strength, but it must be said that the monastic life is not primarily intended to be involved in the developed direct apostolate after the missionary thrust has borne fruit.

There can be a real contradiction between the life expected of secular priests and the active sisterhoods, for example, and that necessary for monastics. The latter are called upon to live in community in one place, which is their permanent home. The Church in the last forty years has put great emphasis on the need for monastics to be faithful to this primary calling, and to be wary of any outside demands that may compromise it.